Permanent Records Lab is a media project focused on the stories and media worth saving. The catch is, it’s hard, if not impossible, to determine which stories, which elements of culture, are worth saving.

In our personal lives we wrestle with this every day. As our photo libraries overflow, as our website domains expire, and as we are chased by the built-in obsolescence of technologies that force us to update every few months, the decision of what to save can be overwhelming.

Our society is faced this same question in a variety of incarnations. Stagnant budgets and threatened cuts to cultural programs such as public media and the arts suggest that our political representatives see cultural production as non-essential and not worth saving. At the intersection of the public and private sectors, powerful media corporations wield their lobbying power to shape the laws and trade agreements that determine how cultural texts become commodified, distributed, and ultimately, saved. We must ask, “Do the values of our current political representation and shareholders of corporations actually serve our long-term cultural values?”

In our consumption of cultural texts as “products”, we are often left to assume the market has solved the riddle of “what matters?”. The best-selling music, films, and media franchises influence artistic expression and media policy for decades at a time. But is the market the most effective tool to preserve culture? Is there something more to culture than “units moved” and “revenues generated”?

Despite the influence of policy and the market, obscure cultural and counter-cultural artifacts routinely rise to the surface. It is a common occurrence for a forgotten or overlooked work to be discovered or rediscovered in a new context. The discovery of our cultural past is about more than just enjoying a song, a picture, or a story. Cultural artifacts teach us about where we came from and the norms we have contended against. In this sense the idiom, “It was ahead of its time” holds implications for the way we approach issues of saving culture.

Whether we look at works from the punk underground of the 90s Midwest, the field recordings of Alan Lomax, psychedelic culture, hip hop, blues, eccentric art, or the outsider journalism of activists, history repeatedly demonstrates that some stories take longer than a single generation to assert their significance. Furthermore, when we turn our attention to the many silenced and marginalized voices throughout history, the work or preserving and transmitting their stories is readily transformed into the work of social justice.

Because of this, media makers must be vigilant archivists. This vigilance not born out of vanity or nostalgia, but out of a sense of duty to the generations to come. While it may be easy to dismiss cultural texts, including one’s own personal media as worthless, someday society (or even a grandchild) might care about what you wrote, how you communicated, what your voice sounded like, what stories you told, and the struggles you faced.

All too often it is catastrophe that makes the significance of protecting culture apparent. In the past decade, we have witnessed the destruction of museums and cultural heritage sites due to violence and natural disaster. In such cases, the gravity of cultural loss becomes palpable. Commonplace events in our personal lives such as hard drive failure also leave us with this “too late” hindsight of loss. We must recognize the importance of building sustainable bridges that will carry our cultural past into the future.

In an era of nearly unlimited digital copying, there is a danger of forgetting just how important the practice of media preservation continues to be. While it may be convenient to trust companies like Google or Apple to manage our cultural lives and the texts we create, we must question, is such trust well placed?

The Permanent Records Lab will explore protocols for how cultural might be preserved in a manner that fosters future discovery. The Lab will explore archival processes across a variety of media. At the same time we will explore contemporary topics such as proprietary restrictions, precarious cloud storage, personal media ownership, DIY and modding culture, digital rights management, and intellectual property. The Lab will seek out storytellers, creators, documentarians, songwriters, designers, illustrators, printmakers and photographers who want to preserve their work and by extension, pass on their stories.

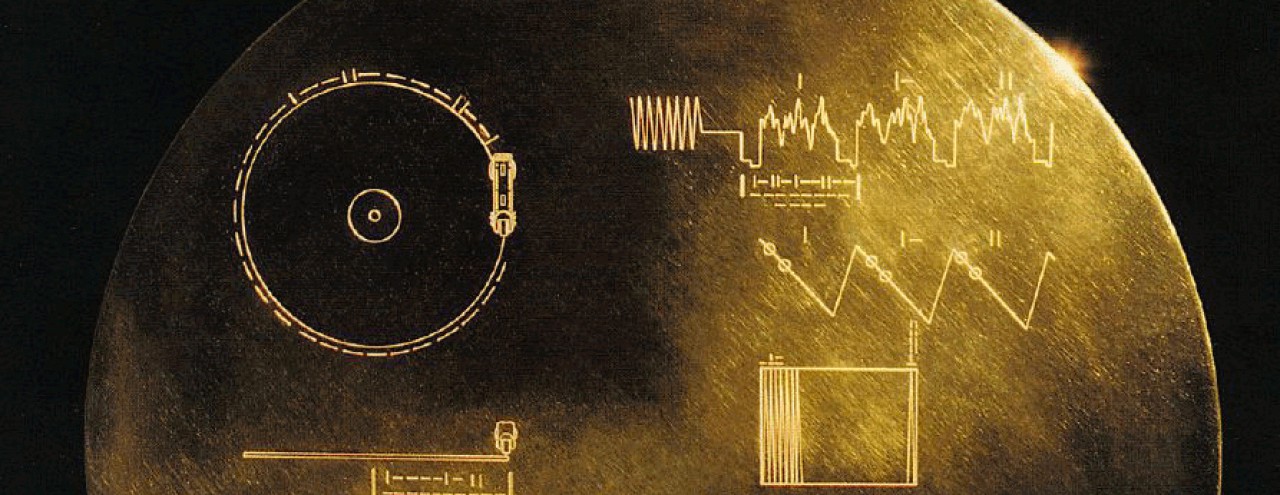

In 1977 the Voyager space craft was sent to explore the outer reaches of the of the solar system and beyond. On board was placed a golden record containing a variety 115 images of the Earth and 90 minutes of sound including a selection of music. The collection was put together by Carl Sagan and encoded in analog format with instructions on how to play the disc. Regarding this “message in a bottle” time capsule, Sagan explained, “The spacecraft will be encountered and the record played only if there are advanced spacefaring civilizations in interstellar space. But the launching of this bottle into the cosmic ocean says something very hopeful about life on this planet.”

And so inspired by this sentiment, that the preservation and transmission of culture across space and time is an act of hope, I hereby commission the Permanent Records Laboratory.

Contact me at stephenbartolomei at gmail dot com to share the story that belongs in your time capsule.